Resonator/slide specialist Eric Sardinas is no blues curator. While he pays homage to the music that inspires him, Sardinas is a fiery super nova that performs with a personalized blend of soulful musicality and showmanship. He and his band, Big Motor, unleash high-intensity blues-rock with an earthy accessibility and raw power driven by his resonator.

How do you approach getting your sound?

The way we approach everything is always organic, fresh, and of the moment. It’s always an honest way of recording. I’ve worked with Matt Gruber for the last two albums, and I like to push myself lyrically and musically. It’s a moment in time. I like to look back, build upon it, and push myself forward.

With the new album, Matt is involved for the third time in a row. I’m excited about it because I look at this as going back to ‘plug in and play.’ We’re about capturing something and having fun with the songs. The album is called Boomerang and it’ll be out in mid October.

You play more than 300 dates each year. You probably have a lot to write about.

It’s a blessing to be able to live the life I dreamed of – to be able to create, whatever the hardships. I have no complaints. My life on the road has its ups and downs, and it’s challenging. My life is music and music is my life, and there’s nothing I would do to change it. I’m very thankful.

You grew up hearing a lot blues players using Stratocasters. What was it about the resonator that pulled you in that direction?

I’ve never gravitated to solidbody guitars. I didn’t connect to it. What I connected with was my love for Delta blues. When I heard a player having something to say and having a connection with the music – that pure, open energy and connection with the instrument, it meant more to me than a Marshall stack. Listening to Charlie Patton, Bukka White, or Skip James play – and connect to that emotion – really made me fall in love. I started on a beat acoustic toy guitar, then an acoustic, and then a resonator. When I was a teenager, I drilled a pickup in because I wanted to electrify what I was doing so I could get off the chair.

I really connected with the resonator because of the romance I had with early players like Tampa Red and Fred McDowell. When slide players like Robert Johnson or Son House would speak on guitar, there was a connection with the voice. When I play electric, I push the instrument that I fell in love with from the Delta, the country, Texas, and Chicago blues, into a place where I found my voice.

Do you do anything special to your resonators?

What I need from my instrument is to take the guitar down to the sweet sound that is pure. I don’t have an interest in piezo pickups or anything like that. I like to work off a straight mic – I work off the cone and use my Volume as a tone control. Whatever the guitar gives me, I give it back.

For amps, I’m using Rivera Amplification. I use the Knucklehead, but it’s slightly tweaked. I like to use a crisscross organization of the speakers in my 4×12’s Greenbacks and straight ’68 Marshalls. I also use a sub for my lows. I like that to move the wind.

Do you use effects?

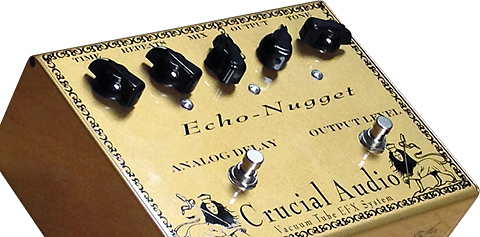

When it comes to effects, I use a Dunlop 95Q wah and an MXR Phase 90. I also use a capo because I use heavy strings; I like the tension because it affords me a little bit more of a direct attack and a little bit less give on the strings with the slide.

I have a signature slide by Dunlop called the Preachin’ Pipe. Dunlop actually took the slide that I had worn down to a nub, weighted and balanced it, and created this slide. I had worn down and played more than 5,000 shows with the slide they copied. On the signature slide, the temperament and the weight is exactly what I like. The wear and tear isn’t there, but that’s up to the player.

What’s your number one guitar?

It’s a cutaway resonator finished in black by Gibson, called the La Pistola. It’s my signature model. The other guitars are the runts that I threw pickups in, I believe in, and drag on the road. We have a heavy tour toward the end of the year.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s December 2014 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

Bryan Sutton ranks as one of the most accomplished and in-demand acoustic players in Nashville. In 1991, fresh from high school, he joined the gospel group Karen Peck and New River. In ’93, he moved to Nashville and joined the band Mid-South for several months before studio work started to dominate his time and began full-time as a studio musician on gospel recordings.

Bryan Sutton ranks as one of the most accomplished and in-demand acoustic players in Nashville. In 1991, fresh from high school, he joined the gospel group Karen Peck and New River. In ’93, he moved to Nashville and joined the band Mid-South for several months before studio work started to dominate his time and began full-time as a studio musician on gospel recordings.

A gold-plated Gypsy-approved tailpiece will accommodate both loop- and ball-end strings. Only the shiny plastic insert (Selmer used plastic, ebonite and rosewood) on the tailpiece detracts from the visual appeal of the guitar body from the front. If this guitar were mine to keep, I’d use a piece of 0000 steel wool to dull the gloss of the insert. This little effort makes it look like ebony from a few feet away.

A gold-plated Gypsy-approved tailpiece will accommodate both loop- and ball-end strings. Only the shiny plastic insert (Selmer used plastic, ebonite and rosewood) on the tailpiece detracts from the visual appeal of the guitar body from the front. If this guitar were mine to keep, I’d use a piece of 0000 steel wool to dull the gloss of the insert. This little effort makes it look like ebony from a few feet away.