I hadn’t seen Wayne Kramer, lead guitar for Detroit’s legendary MC5, in 25 years, yet there we were shaking hands and hugging each other, trying to get in as much reminiscences of the old days in the Motor City before he went onstage. His band was the headliner at a massive labor march in Detroit sponsored by the national AFL/CIO to support the city’s striking newspaper workers. Kramer answered the call for entertainers.

I was the MC for the music that followed a couple dozen barnburning speeches by national and local union leaders. When I saw Wayne before the show, he was fashionably dressed in black. Later, as he jumped confidently onstage, announcing he was ready to play, he was sporting a shocking pink tuxedo.

“You’re stylin’,” I whispered to him.

“I ain’t into no grunge,” came the reply.

The MC5, originally formed as the Motor City Five in 1964, became Detroit’s major act by 1967 in a scene crammed with talent including Iggy and the Stooges, Ted Nugent, and Bob Seger. Heralded as both a seminal ’60s rock band and some of rock and roll’s original bad boys, the lineup was Rob Tyner (vocals), Wayne Kramer (lead guitar), Fred “Sonic” Smith (rhythm), Michael Davis (bass), and Dennis Thompson (drums).

The band’s signature song, “Kick Out the Jams” using the then-forbidden word “mother@!#*er,” combined with its wild stage performances and connection with charismatic manager John Sinclair’s White Panther Party, honed its badass image but insured the boys were in constant trouble with cops, club and record store owners, and even their own record label. The band entered rock history for being the only act willing to brave the Chicago cops and the National Guard by playing for protesters at the tumultuous 1968 Democratic Convention.

Its discography includes Kick Out The Jams (Elecktra, 1969), recorded live at Detroit’s Grande Ballroom, Back in the USA (Atlantic 1970), and the avant-garde High Time (Atlantic 1971).

After the band’s dissolution in ’72, Kramer turned to drugs and alcohol, habits that culminated in a cocaine trafficing bust for which he served 26 months in federal prison. Today, 20 years after he went to prison, his career is back in high gear with four recent CDs for Epitaph – The Hard Stuff (1995), Dangerous Madness (1996), Citizen Wayne (1997), and LLMF (1998).

Kramer feels great and is playing better than ever. VG had a talk with him following his set at the labor rally.

Vintage Guitar: I’m sure you’ve heard it said many times that the MC5 was one of the bands that defined a genre. Do you feel you were?

Wayne Kramer: Yeah; you can connect the dots from the MC5 and the Stooges to the New York Dolls to the Ramones to the Sex Pistols to the Clash to Black Flag to Offspring. But the truth is, the legend business actually doesn’t pay that well. Outside of Detroit, the MC5 was never accepted by the music world. In California, the ’60s hippies really weren’t interested in this band from Detroit, this industrial city – “they make cars in Detroit, don’t they” – you couldn’t do anything cool there. That made us fight back even harder.

Also, we came out with spangly clothes and big Marshall amplifiers and talking about “kicking out the jams.” The hippies didn’t want to know about that; they were just learning how to market three days of peace, love, and music.

They were too busy listening to Jesse Colin Young. Still, your influence went well beyond your roots. I’ve heard Mick Jagger say the MC5’s stage performance influenced him.

The musicians have always been cool about it. Part of my job is to tell the story of the MC5. It’s the last great untold story of the ’60s; the missing link in the history of our culture. There was a unique, vibrant, alive scene here in Detroit that really didn’t happen any place else. It was real specific to Detroit with the confluence of a lot of different pressures and events. The auto industry was booming; the city was a place where Southerners came, along with people of color, and we all lived together, and everybody had jobs.

You were a bunch of white guys from Lincoln Park, a working-class suburb, one of the “…grease pits of FoMoCo city,” as you used to say. Where did you come up with the style of music and stage presence you were noted for?

It came up out of the streets of Detroit. The music we were exposed to growing up in the shadow of Motown Records, and hearing what those musicians were playing, like the great Motown recording band of James Jamerson and Bennie Benjamin. Also, on Detroit radio we were exposed to a lot of black music, including gospel. There was this thread I gravitated to in certain kinds of music that had a commitment and a passion about it we came to call “high energy” music. It was visceral. It wasn’t an intellectual music, it wasn’t sensitive; it was raw and it was emotional. I searched out that kind of music and found it in James Brown and the guitar work of Chuck Berry.

Later, when we met John Sinclair, he exposed us to the free-form jazz of Sun Ra, John Coltrane, and Albert Ayler. And the connection from Chuck Berry to John Coltrane made perfect sense to me. It all had this high-energy idea which is a very Detroit concept.

What was your first guitar?

It was a Kay, sold by Sears; a low-end, cheapo version of what Gibson was making; a steel-stringed, acoustic, f-hole guitar. It was very, very rough to play for a 9-year-old, to hold the strings down to make the chords.

When we moved to Lincoln Park, my mother could afford my first electric, a solidbody Sears Silvertone, two pickup, black with white trim, either a Jet or Rocket, some ’50s-era name. It was actually a quality guitar for a $125.

What did you use once you became guitarist for the MC5?

Equipment was always a big problem. Our people were all working-class folk; you could squeeze a guitar out of them, but getting amplifiers was something else.

We met a guy who wanted to manage the band and we convinced him we needed equipment, so he took out a bank loan for us. The first wave of the British invasion had just hit and we discovered these Vox amps the Beatles played. Before that, Fender was the state-of-the-art. When we purchased these Voxes, it was like the MC5 took a quantum leap from being this ragtag gang from Lincoln Park to being a professional band.

Fred Smith and I got 100-watt Vox Super Beatle amplifiers. Before the Beatles they were just called AC-100s. They were really great; nothing in America had 100 watts. The biggest amps were Fender Dual Showmans at 65 watts with two 15″ speakers. The Super Beatles were 100 watts with four 12″ speakers and two high-frequency horns mounted in a tubed frame cabinet you could tilt back. It was a huge piece of machinery and very intimidating because it was black. We had two of them; a T60, the transistor bass amplifier with a 15″ and 12″ speaker and two Vox columns for our PA system with six or eight 10″ speakers mounted on chrome stands that went on each side of the stage. In those days, that was the state-of-the-art PA system; there was no such thing as monitors or side-fills.

What was the importance of the Vox amps?

They made us the loudest band in Detroit; a title we wore with great pride. Nobody could approach the volume at which we could perform. And we discovered we could push the sound beyond what had previously been accomplished with electric instruments. Because of the incredible volume we could push it into the level of feedback and distortion on a brand new scale.

The amps were designed for use in Europe, which has different power ratings. We found if you set the switch down the scale from the American settings, you could get more distortion at lower volume. The more we experimented with them, the more we found we could get into some brand new areas. We sat the guitars down once to take a break to go make some peanut butter sandwiches and the guitars began feeding back by themselves. We were pretty sure we had discovered the power to change the universe.

The Voxes were really a part of the MC5 legend being established.

What guitars were you playing during the height of the band?

I had traded the Silvertone for a Fender Esquire, which is the same as a Telecaster except it had one pickup. Finally, we got the manager to spring for another bank loan and I got a Gibson ES-335, and Fred Smith got a Gretsch Tennessean, and the bassist, a Fender Precision.

Of course, the guy who took out the loan expected us to make the payments, but we were completely-crazed teenaged lunatics and didn’t even consider the possibility of making payments. One night, at Detroit’s Ford Auditorium, the MC5 was opening for Jefferson Airplane – our biggest gig to date – and the guy shows up with two Detroit cops and a court order to repo our equipment. The promoter paid off $200 so we could use them for the night. But then they took it all, including the Voxes and the guitars.

What did you do for new stuff?

By then we were involved with John Sinclair and the White Panthers, and we started to see Marshall amps coming over from England. Cream played them; we knew Jimi Hendrix used them because we had opened for him. So we bought a load of the original 100-watt Super Lead heads. We got six of them and two 200-watt bass heads. They were terrific-sounding amplifiers, but incredibly inconsistent; we blew them up regularly. You might get two or three shows out of them and then they’d go up in smoke. We’d have two sets of Marshalls with us on the road and one set in the shop all the time.

What guitars did you feed through them?

I saw Jeff Beck playing an old Les Paul, so when I met a kid whose father had one, I traded my 335 for the Les Paul, one of the originals. Unfortunately, it was stolen after a gig, and in fact, almost every guitar I’ve ever owned has been stolen. Then I started playing a Firebird, then a Stratocaster, and I stuck with those for a long time. I had the Strat hotrodded with a Gibson humbucking pickup to stay competitive with the sound level of Fred’s Gibson. I used a Big Muff distortion pedal and used that during the “Kick Out the Jams” era, since the wah-wah pedal hadn’t been perfected yet. I also played a Telecaster and one lucite Dan Armstrong that sounded pretty good.

You’ve recently gotten back together with Dennis Thompson, the MC5’s drummer, in Dodge Main [the name of a long-shuttered Detroit auto plant] who told me, “This is the year of the MC5,” referring to a documentary about the band. How do you nurture the past, but live in the present?

I honor the past. But it’s a dilemma for me as a musician, living in today’s kiddie culture, to do rock and roll and find some meaning in it. We live in a society and a time that doesn’t honor age, that has no concept of the history of culture; 25-year-olds are making multimillion-dollar decisions.

When you were 25 or when Mick Jagger or John Lennon were, didn’t the industry have the same qualities, admittedly involving a lot less money? Also, at the last Rolling Stone concert I attended, it seemed three-quarters of the people there were under 30.

This is the good news. Our cultural idols – the icons – don’t have to be just James Dean or Kurt Cobain; they’re also Picasso and Howlin’ Wolf. I have to be able to do this work as an adult and still have passion about it, still be vital and still rock and make records that have some meaning. This is still my idiom and I am determined to say something of value in it.

Do you have any bitterness the MC5 didn’t receive the recognition it deserved?

None. I think the MC5 gets its props. I get it all the time, all over the world. I was in Paris at a press conference and the interpreter pulled me aside after and said, “Wayne, I just wanted you to know how much my MC5 records mean to me. They’re part of our history, too.” It’s not a story that’s well-known to your average 17-year-old poo-butt, jean-wearing skateboard suburban kid. He doesn’t know the story of the MC5; it’s a story told by oral history, tribe by tribe. One group of guys learns about it and they tell their friends, “Did you ever hear about the MC5? They were crazed; they were from Detroit; they had guns and they were a rock band.”

The story leaks out here and there. Books like Legs McNeil and Jillian McKane’s, Please Kill Me, tells some of the story, and Fred Goodman’s book, Mansion on the Hill, tells more, and our documentary will tell some, too.

Do you play guitar better than you did in the MC5 days?

I play better. I write better songs, I’m a better singer. I didn’t burn out. I’m 49 and I wake up every day thrilled to do the stuff I do. It’s is more stretched out than it ever was. Traditionally, when you reach your middle-adult stage, that’s when you come into your power, that’s when you really get a handle on it.

You’ve attained much of your fame based on your stint with the MC5, but your latest CDs don’t sound like you’re relying on 25-year-old licks.

I’m a musician with big ears. I hear everything and listen to everybody. Music has the ability to reinvent itself and recontextualize itself. There’s things I hear, other musicians that influence my work; I’m a man in touch with my times. I’m trying to pay attention to what’s going on out there.

What do you think when bands like the Presidents of the United States cover MC5 tunes?

I like it a lot. The Presidents wrote me a letter asking me if they could change the lyrics to “Kick Out the Jams,” and in the beginning I said no, even though usually I never say no to anybody. I thought, “It’s a sacred song; you can’t mess with it.” But the more I thought about it I realized, I’m starting to sound like a parent or something. So I told them it was okay.

What did they want to change?

They had written some new verses. I didn’t get it. I was just reading their text and thought it was irreverent and making fun, but that’s the idea of the Presidents of the United States; they’re an irreverent group. They’re kind of a fun, lightweight, disposable band, but I was thrilled they decided to do the song.

That song, with its famous opening shout by the late Rob Tyner, “Kick out the jams, mother@!#*er,” got you guys in a lot of trouble when you played it at Detroit-area clubs. Arrested, beaten up by the cops, and the plug pulled on your shows.

It was the call to action, the battle cry; “Man the barricades!” A lot of times the club owners would tell us, “If you sing that song with the swear word in it, we won’t pay you.” Then, Rob would get so excited in the heat of the moment, he’d say it anyway and we’d walk away broke for the night. We had constant problems with the police. They’d search our van, stop our shows, tell us what we could and couldn’t play. One time our show was surrounded by Oakland County sheriff’s deputies who threatened to bust us if we sang it, so Rob yelled, “Kick out the jams. . .” and the crowd finished the sentence.

You guys changed some pretty serious lyrics yourselves on “The Motor City’s Burning,” by bluesman John Lee Hooker, his song about the ’67 Detroit riot. Hooker sings at the end of his song, “Johnny Lee is getting out of here,” but you changed it during your performance at the Grande.

Yeah, I was shouting, “It’ll all burn, it’ll all burn.” Once a militant revolutionary, always a militant revolutionary. You don’t turn in your card.

How do you feel about your latest studio release, Citizen Wayne?

It’s my latest science. With my history of activism in the work, my political consciousness – I come from a political time and a political band – I think, “How do I do this work today as a thinking adult? Is there a place for me to compete with the Spice Girls?”

I’d like to think if I make the kind of music I believe in, and the kind of sounds and the kind of songs I think are important and beautiful, maybe there’ll be some other people out there who think so too.

Visit www.epitaph.com for more information on Kramer’s recent releases.

Kramer Kicks It with Cheap Trick

Cheap Trick recently played a three-night engagement at the House Of Blues in Los Angeles, where the band performed its first three albums on successive nights in early October.

Epic/Legacy recently reissued all three albums with digital remastering, liner notes, and outtakes, and the live show included songs even longtime fans have seldom, if ever, heard in concert, including “So Good To See You,” from In Color, and two from Heaven Tonight; “On The Radio,” and the title track. Bassist Tom Petersson sang lead on a cover of Lou Reed’s “Waiting For The Man/Heroin,” and his own “I Know What I Want.”

Former MC5 guitar god Wayne Kramer (a friend of CT from its Midwest days), who opened the first night’s show, returned during the finalé to lead Cheap Trick through a sendup encore of the MC5’s signature “Kick Out The Jams.”

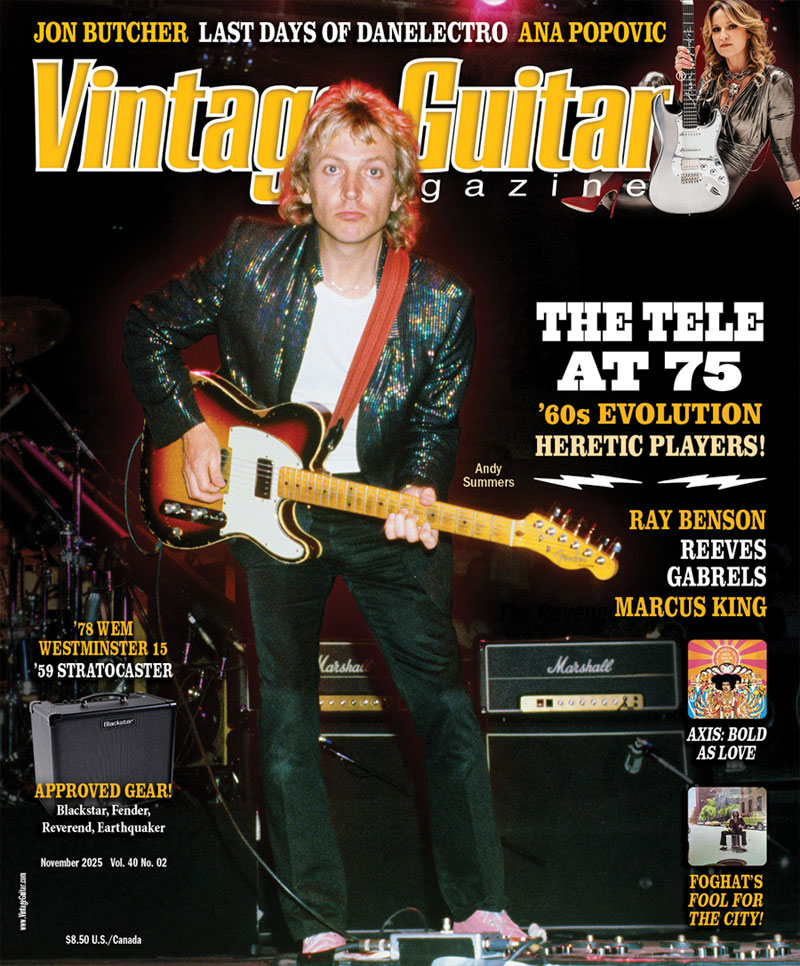

Wayne Kramer with a custom set-neck Fender Telecaster with dual humbucking DiMarzios (complete with coil tap). Photo: Margaret Saadi, Musclemusic.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Dec. ’98 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.